Forsyth Humane Society is celebrating Black History Month by spotlighting Black men and women who have made great contributions to the animal welfare world.

The Humane Society of the United States reminds us that, “the history is complex: The modern American animal welfare movement emerged in the wake of emancipation, and from the beginning, the movement’s leaders drew comparisons between human slavery and animal abuse. (Paula) Tarankow’s research shows that using the experience of Black Americans as a metaphor for animal causes ignored the fact that Black Americans were still suffering the very real effects of slavery. In working with white animal advocates, Black animal advocates were typically discouraged from raising the subject of the racism they continued to experience in their daily lives, essentially forcing them to choose: If they wanted to raise their voices for animals, they would have to keep silent about racism to avoid making the largely white, middle-class “mainstream” of the early movement uncomfortable.”

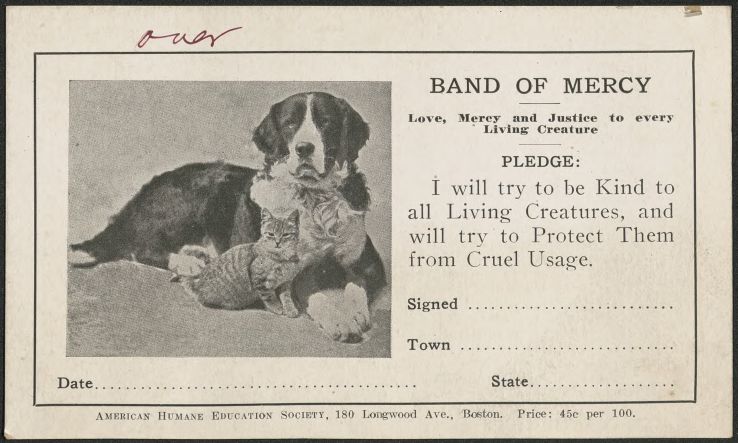

The Humane Society of the United States continues explaining how among the messiness of the movement, “Black reformers continued to advocate for animals even as they themselves continued to be denied their full humanity. Rather than use liberation from slavery as a metaphor for animal rights, Black reformers saw kindness toward animals as an extension of civil rights activism, emphasizing that kindness toward animals and kindness toward human beings were linked. One of the most prolific platforms for this work involved the Bands of Mercy program, of the Massachusetts SPCA. Bands of Mercy were humane education groups, and members participated in meetings and community service that centered around being kind to animals. Many participants were children who took lifelong pledges to be kind to animals and to try to prevent harm to all living creatures. Black advocates in several Southern states were highly involved with the program as teachers and organizers and worked as field agents.”

F. Rivers Barnwell of Texas approached kindness to animals as a social justice project promoting competitions at African American schools to build birdhouses to support wildlife, and spoke to soldiers about the humane treatment of horses used in World War I.

The Rev. Richard Carroll, a prominent South Carolina reformer, born into slavery, also established Bands of Mercy as he worked to create a more humane world in his work from around 1910 until he died in 1929. His son, Seymour Carroll, built on this legacy, campaigning against the use of steel traps for wildlife in South Carolina.

Perhaps the most famous Black leader in the early animal welfare movement was a formerly enslaved man named William Key. Mr. Key performed for hundreds of thousands of people along with his horse, “Beautiful Jim Key”. The horse responded to prompts and requests from the audience, showing his intelligence. Key and his horse modeled a beautiful example of the human-animal relationship not sustained through violence. A core part of their act emphasized that Beautiful Jim never felt the sting of a whip—instead, he’d been trained through patience, kindness, apples, and sugar! By the end of Key’s career in 1909, more than a million children had taken the Jim Key Pledge to be kind to animals.

As the movement progresses, we see a more diverse population of Doctor of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Iverson C. Bell (1916-1984) started his education at Kansas State University, served in the US Army, returned to Wayne State University, and on to Michigan State University where he earned his DVM. He ran a thriving private practice for 35 years, valuing education and political leadership positions including those for fair housing, and criminal justice. He was honored with an ambassadorship to Nigeria by President John F. Kennedy and worked throughout his life to combat discrimination of his era.

Alongside Dr. Bell, was Dr. Frederick Douglass Patterson (1901-1988) the founder of the Tuskegee School of Veterinarian Medicine which, to this day, has graduated an estimated 75% of African American veterinarians. Named after the famed journalist and anti-slavery leader, Dr. Patterson was raised by his older sister after being orphaned at the age of two. He attended Iowa State College where he earned his DVM and began teaching at Tuskegee University in 1928. Among his many accomplishments was the founding of the United Negro College Fund which remains a major financial supporter of Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

Just after Dr. Patterson began teaching at Tuskegee University, and while Dr. Bell was progressing in the movement towards equality in veterinarian medicine, Dr. Alfreda Johnson Webb was growing up in Alabama. She completed her Bachelor of Science and attended the Tuskegee University School of Veterinarian Medicine. In 1949 she graduated alongside Dr. Jane Hinton as the first African American woman to graduate from veterinarian school. Dr. Patterson was also the first licensed woman to practice veterinarian medicine in the United States. She was a biology professor at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University from 1959 to 1978, where she was a member of the planning committee that founded the School of Veterinarian Medicine of North Carolina State University. She held many honors and served on many committees and is a true pioneer in our field and a champion of justice and democracy.

At Forsyth Humane Society we are committed to creating conditions within our community that foster the compassionate care of pets and the people who love them. We strive to continue to learn more about and work alongside the people of color who have and continue to positively impact the animal welfare community right here in our backyard to pave a path together, towards a humane society. Here’s to taking, and continuing, the tradition of the Jim Key Pledge of being kind to animals, and people!

Sources: The Humane Society of the United States, Faithful Friends Animal Society, Michigan Humane Society, and VCA Animal Hospitals